FIVE ANALOG IDEAS TO TRANSFORM YOUR DIGITAL WORLD

Analog/Analogue/Analogy– to copy, record, build, capture a likeness of something using a different medium than the original. Converting one thing into another while retaining its essence.

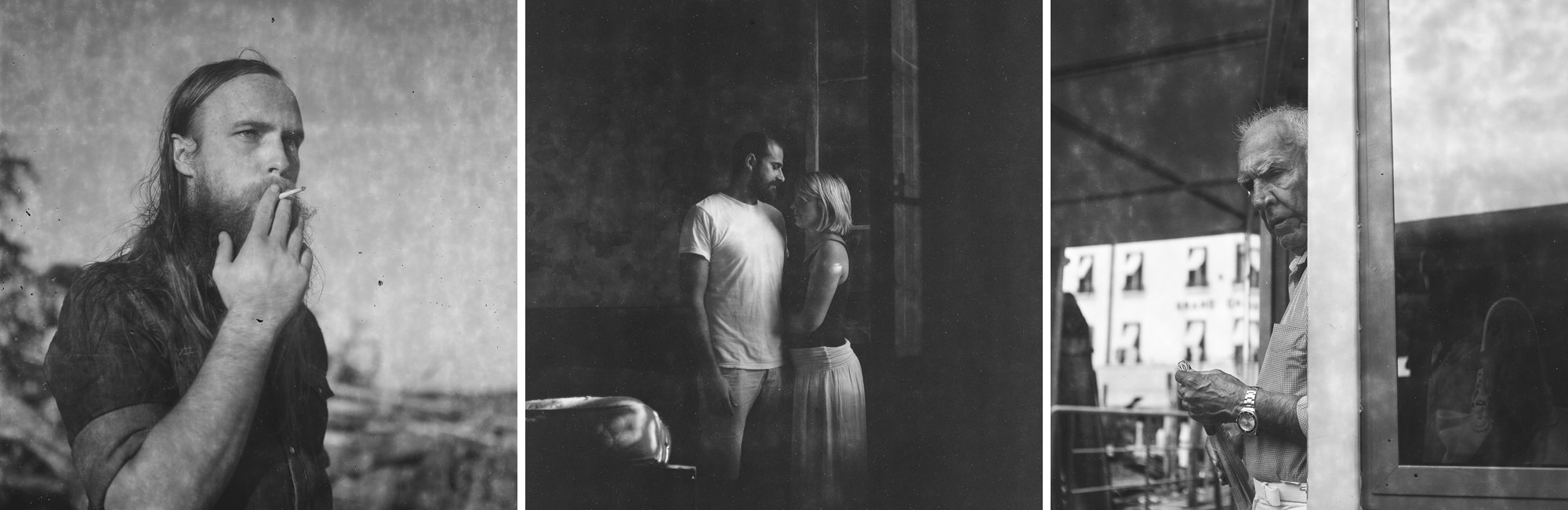

There’s no doubt the creative world has experienced a huge resurgence of analog methods in the last few years. Film-makers crafting gloriously-made features on film, musicians recording fresh albums on old tape and, in particular, photographers rediscovering the tools, processes and methods at the root of their craft – namely, shooting on film. In particular, shooting film by wrangling a weird, old, half broken-down treasure of a camera that they scored off eBay for waaay too much but that occasionally produces a crazy level of magic that keeps them coming back for more… welcome to the game.

Now there’s a million good reasons why I’d suggest you pick up an old camera and bang a few rolls out, but probably the most overwhelming one is not for the end results, but rather to learn a handful of principles from the analog world that have been the fountainhead for visual art creation in the last half of the 20th century. These ideas also happen to translate to the digital world very easily and can completely transform your creative process.

Honestly, you don’t even need to shoot film to get a hold of this stuff and put it into action tomorrow – although that wouldn’t hurt.

Principle No. 1 – Calibration

The very concept of having to keep something ‘calibrated’ is an idea that belongs to the analog era. Machinery, things that copy, non-digital parameters governed by dials that can get out of whack and have to be brought back to accuracy. Like you.

Have you ever wondered why you like the stuff you do? Why, when you’re editing colour and tone and contrast, that the Lightroom slider stops in a certain place and it feels ‘right’ to you? Because you’ve calibrated yourself. You’ve watched and looked and absorbed and listened and all of that info has gone inside… and it comes out as your work.

Here’s the thing: analog made you and you didn’t even realise. The visual revolution that analog technology brought about in the last half of the 20th century was an absolute sea change for our species. It was the advent of colour imagery, cinema and television, magazines and newspapers – the way we experience visualness. After WW2 the planet was swamped with imagery everywhere you looked: from advertising to magazines to movies and album covers and colour pictures in newspapers, to cheap art that you could hang on your wall at home and, most importantly, to a whole cohort of visual artists who invented the rules for this new medium. People like Ernst Haas, William Eggleston, Inge Morath, Saul Leiter, Herzog, Shore and hundreds of others. Brilliant men and women who grabbed the raw materials of a new visual age and transformed the way we see. These men and women were like the Hendrix of imagery, the Lennon/McCartney of seeing. They grabbed hold of new tools and they did wild things with them and we’re still catching our breath 50 years later. Everything you see on a screen in 2020 has its roots in that radical era.

The line between these innovators and you is very short and very straight. Even if you haven’t heard these names, the people who are YOUR heroes have, and they’ve passed that revolution on to you. These innovators calibrated how you see and what you think is possible. And, in turn, THEY were calibrated by the medium they worked with, by the colour and tone of film emulsions like Kodachrome and Verichrome Pan. The body of imagery that we inherited from the 20th century calibrated the very way our species sees light and colour, how we interpret our own visualness, how we see. And that, in turn, informed a generation of artists who held it up as a standard; and that generation of artists are currently in their absolute cultural prime and influencing… you.

The analog world set a standard for colour and tone and we’ve adopted that gold standard as our normal; and we’re still chasing it every single day.

There’s a well-thrashed saying in the creative world that ‘you are what you eat’ – often re-interpreted as ‘if you don’t like your output, change your input’. All it means is that you’re an analog machine made of flesh and blood and emotion that needs to be constantly calibrated, nudged, corrected, fed good references and re-aligned with the right stuff. You need to stay calibrated by putting good stuff into your creative mill.

Get calibrated, feed yourself, nudge your dials, look at why you think and feel and love the things you do, because inspiration is far too important to be put in the hands of an algorithm.

Principle No. 2 – Constraint

If there’s one analog idea that’s easy to get your head around it’s the concept of constraint: of limited supply, of 12 6X6 shots on a roll of 120 film, of three minutes of footage on a roll of Tri-X Super 8. When you come from the green-fields endlessness of digital 1’s and 0’s, to purposefully limit yourself to just a handful of shots seems like madness. Surely at the very heart of being creative is the idea of endless raw material? Eternal chances at perfection? Nah bro. Turns out a constant supply of blank pages is crippling for most artists. Constraint is glorious. Limits are focusing.

In fact, when you come from an endless supply of digital opportunities, to suddenly have limited ‘ammunition’ in the camera is focusing as hell. The thrill is back and every frame has to pull it’s weight. You’re looking for dynamite rather than just prospecting. The world slows downs and speeds up all at the same time and NONE of that is anything to do with having film in the camera, but it’s all to do with the idea of constraint.

Go to an architect and ask them to design you a house. The first thing they’ll ask you about is the constraints: ‘What’s wrong with the site, what are the limitations, what does the council say you can’t do, how pesky are the neighbours, what’s the dirt like, how high can you build, what’s the budget?’ They want to see all the problems so they can start to figure out wonderful ways to solve them. That’s where innovation and breakthroughs come from, by solving unique sets of problems and forging new paths.

Take your favourite musician and the famous ‘second album’ syndrome. A debut album is the product of low budgets and slaving away in your bedroom; being broke and not having anyone believe in you – it’s art made on a strict diet of constraint. And it changes people’s lives, it’s the soundtrack to summers and broken hearts and road trips and obsession. And then the label says ‘Make us a kickass second album like that first one, limitless budget, all the people you want, sky’s the limit…’

They bomb. Nearly every time.

Think of it like this. Firecrackers and bullets. You put a pile of gunpowder on the table and light it, you get a puff of smoke. Wrap that gunpowder in cardboard and you get a bangin’ lil firecracker. Constrain that small pile of gunpowder in a brass tube and stick some lead on the end and you’ve got a bullet with ridiculous potency that’s able to take life, change history, and threaten with an absurd level of power.

Constraint is power, not limitation. Having less options is focusing, it’s exciting, and it leads to innovation not stagnation.

Principle No. 3 – Visualising

Full disclosure: We shoot loads of film on weird old machines. We also shoot a huge amount of work on magic digital tools made by our friends at Canon.

If you want to understand the absolute joy of digital, pick up a 5D to shoot a wedding day after you’ve spent two weeks shooting jobs in difficult light, entirely on film, on 1950’s cameras, without a meter. THERE’S A SCREEN! HOLY SWEET MOTHER OF LOOKING, IT HAS A SCREEN! It’s easy to forget what an absolute breakthrough it was to suddenly be able to test the light, instantly test ideas, see what you shot, to meter simply by looking at the back of the camera rather than taking a million readings. Digital photography, a screen on the back of the camera, was a breathtaking game changer.

Yet at the same time we lost the ability to see for ourselves when we started letting the camera do the seeing. In the digital world your natural response to an interesting scene or nice light is to test it with the camera, see what the camera sees, ask the camera if the idea works or it looks good. That’s before your imagination has even kicked into gear or you’ve really investigated the way the light falls, or the human interaction and the politics of simply being in the room. Before your idea has even had a chance to take it’s first breath, you’ve instantly put it to the test and moved on. The start of the digital creative process is to use the camera.

Yes it’s efficient, yes it’s fast, yes it means you’re guaranteed an effective result.

But contrast that approach with how it feels to walk into a room with only 36 frames up your sleeve. You stop, you look, you pre-visualise. You search for the human magic, the light magic, the spatial magic. You move your body around, you think about what you’d meter for, about how the light moves, and while you’re trying to slow everything down your natural creative process kicks in. You breath in, you breathe out, you see things you hadn’t seen at first, you solve problems, you discover options. And then the very last thing you do is put the camera up to your face and hit go on a finished idea. Making the photograph comes at the very end of the creative process.

In one of these scenarios you’re the master of the camera, and in the other scenario the camera is the master of you. Honestly, it’s not a film thing – it really doesn’t matter what the camera’s loaded with, it’s a process thing. It’s a seeing thing. It’s about letting your eyes and mind and heart engage and do the work, to pre-visualise and problem solve. You are greater than the screen. Give your mind some breathing space to develop ideas before you test them with the camera and your work will take massive leaps forward. It’s ‘How To See Again 101’.

No. 4 – Expectation

Or, the joy of ‘What you see is what you get’. When people say they love the imperfections in film, what they’re really saying is ‘I only had 36 frames to look at so I kept looking until I realised I loved them all…’

That’s not a digital vs analog thing, that’s a limited inputs thing. Go eat dinner at a low end buffet and you’ll pile your plate high with all sorts of things that don’t belong together and you’ll stuff ‘em in your mouth and have no idea what you’re eating. Then go have lunch at a high end restaurant where everything is carefully considered and you’ll find that there are very few things on your plate; a limited palette of flavours that focuses your tastebuds and your brain on discovering everything there is to discover. Eat a simple meal at an Italian grandma’s kitchen table and you’ll see three ingredients, and it’ll change your life – “But how can tomatoes taste so good?!” Well, it starts with only having tomatoes on the plate.

Expectation is everything. When you shoot a thousand images it’s easy to forget what you were trying to achieve, but when you shoot 36 (or 24 or 12) you can remember what you were hoping for – even after it’s been away at the lab for three weeks. And when you sit down to consider the result (even if it’s disappointing) you come to the bottom of it very fast. So you go back and look again, and you start to see more, and you start to take it at face value, and you fall in love with it.

How many works of digital art have you culled away into the bin after considering them for a nano-second, never to be seen again? And how many times have you looked at a roll of film you shot, hated it, and been left disappointed? Then, on second glance a week later, you realise that every frame is a masterpiece…

Expectation and the lesson of analog is simply to expect more, and to keep looking until the frames start to give more.

No. 5 – Process

Workflow is a catchy lil word that we use to mean moving thousands of files from the camera, through processing, and into an online gallery, but we should really be using it to describe the entire process of how we generate ideas, work them up into concepts, and then make something tangible out of them.

This is the place where we really see a very different analog principle in play and where we see all of these four earlier principles combine into a wildly different process of making work than we’re used to in the digital world. Forget photography for a second (it’s a little too close-to-home) and let’s think about the creative process in making a musical record:

The digital method of musical collaboration is wild. Simply insane. You can have four people in a band, they can all be in far flung corners of the world, sending each other files, listening on headphones, writing songs as you go, piecing them together out of fragments of melody, figuring out what works and what doesn’t. Recording endless tracks over the top of each other’s ideas and sampling sounds and manipulating weird instruments to piece together a bangin’ track bar-by-bar (or even note-by-note). It’s cheap. There’s no time constraints. And you can make endless changes until you hit the right thing.

Now take the analog version of that. You’re gonna record your album on tape, so you have limited tracks to work with and a limited amount of takes you can do (because if you keep re-recording over the same piece of tape you’ll eventually ruin it). So let’s say you’ve got 24 tracks and three takes. The first thing you need is finished songs. So you demo, you write, you refine, you listen to each other. You have to be in the same place, the same room, you argue, you fight, you make up, you get drunk, you write the song of your life. And then you need to rehearse this thing because you’ve only got three takes to get it right. So you hire an old house in the country where you can get loud, you work and re-work and lose your way and find it again. You look across the room at your friends and realise that this is one of the great moments of your life. And you absolutely NAIL it. And then you go into a studio, or a great sounding room, and you fill up all 24 tracks with carefully chosen mics on deliberately crafted instruments. And then you breathe in, you look at each other, and you hit three takes of this masterpiece you’ve crafted together – they’re all different and imperfect – and you choose one that FEELS like it captured the magic that went into the whole process.

You’ve made two VERY different sounding songs with these two very different processes. One analog, one digital. And the medium really doesn’t matter, because the thing that made them so different is the process. And when you play those two different songs to your fans, no-one’s saying ‘can you hear how different digital and analog sound?’ Because it’s nothing to do with the sound, and EVERYTHING to do with the process. The results are so different you can’t even compare them.

Apply those lessons to image-making: to preparation, to idea development, to expectation and constraint, to calibrating yourself and working with and alongside other humans to figure out how to bring something to life. To realise that the magic’s in YOU, not in the equipment, not in the medium.

You can change your process at any time to embrace any of these wonderful ideas – regardless of what machines you’re using, regardless of what the camera’s loaded with – to make art. The magic is in you to put something different into action in a novel way, to move forward, to cut a new facet on the diamond of your art and let the light in in a whole new way.

GEEK DETAILS:

All colour images shot on Kodak Portra 400, and B&W images shot on Kodak 400TX or Verichrome Pan, with Rolleiflex 3.5B or Mamiya 6, at box speed.